-

Trail goes cold in UK abandoned babies mystery

Trail goes cold in UK abandoned babies mystery

-

Japan's Takaichi set to call February snap election: media

-

Scientist wins 'Environment Nobel' for shedding light on hidden fungal networks

Scientist wins 'Environment Nobel' for shedding light on hidden fungal networks

-

From bricklayer to record-breaker: Brentford's Thiago eyes World Cup berth

-

Keys overcomes serve demons to win latest Australian Open warm-up

Keys overcomes serve demons to win latest Australian Open warm-up

-

As world burns, India's Amitav Ghosh writes for the future

-

Actor Kiefer Sutherland arrested for assaulting ride-share driver

Actor Kiefer Sutherland arrested for assaulting ride-share driver

-

Gilgeous-Alexander shines as Thunder halt Spurs losing streak

-

West Bank Bedouin community driven out by Israeli settler violence

West Bank Bedouin community driven out by Israeli settler violence

-

Asian markets mixed, Tokyo up on election speculation

-

US official says Venezuela freeing Americans in 'important step'

US official says Venezuela freeing Americans in 'important step'

-

2025 was third hottest year on record: EU, US experts

-

Japan, South Korea leaders drum up viral moment with K-pop jam

Japan, South Korea leaders drum up viral moment with K-pop jam

-

LA28 organizers promise 'affordable' Olympics tickets

-

K-pop heartthrobs BTS to kick off world tour in April

K-pop heartthrobs BTS to kick off world tour in April

-

Danish foreign minister heads to White House for high-stakes Greenland talks

-

US allows Nvidia to send advanced AI chips to China with restrictions

US allows Nvidia to send advanced AI chips to China with restrictions

-

Sinner in way as Alcaraz targets career Grand Slam in Australia

-

Rahm, Dechambeau, Smith snub PGA Tour offer to stay with LIV

Rahm, Dechambeau, Smith snub PGA Tour offer to stay with LIV

-

K-pop heartthrobs BTS to begin world tour from April

-

Boeing annual orders top Airbus for first time since 2018

Boeing annual orders top Airbus for first time since 2018

-

US to take three-quarter stake in Armenia corridor

-

Semenyo an instant hit as Man City close on League Cup final

Semenyo an instant hit as Man City close on League Cup final

-

Trump warns of 'very strong action' if Iran hangs protesters

-

Marseille put nine past sixth-tier Bayeux in French Cup

Marseille put nine past sixth-tier Bayeux in French Cup

-

US stocks retreat from records as oil prices jump

-

Dortmund outclass Bremen to tighten grip on second spot

Dortmund outclass Bremen to tighten grip on second spot

-

Shiffrin reasserts slalom domination ahead of Olympics with Flachau win

-

Fear vies with sorrow at funeral for Venezuelan political prisoner

Fear vies with sorrow at funeral for Venezuelan political prisoner

-

Pittsburgh Steelers coach Tomlin resigns after 19 years: club

-

Russell eager to face Scotland team-mates when Bath play Edinburgh

Russell eager to face Scotland team-mates when Bath play Edinburgh

-

Undav scores again as Stuttgart sink Frankfurt to go third

-

Fuming French farmers camp out in Paris despite government pledges

Fuming French farmers camp out in Paris despite government pledges

-

Man Utd appoint Carrick as manager to end of the season

-

Russia strikes power plant, kills four in Ukraine barrage

Russia strikes power plant, kills four in Ukraine barrage

-

France's Le Pen says had 'no sense' of any offence as appeal trial opens

-

JPMorgan Chase reports mixed results as Dimon defends Fed chief

JPMorgan Chase reports mixed results as Dimon defends Fed chief

-

Vingegaard targets first Giro while thirsting for third Tour title

-

US pushes forward trade enclave over Armenia

US pushes forward trade enclave over Armenia

-

Alpine release reserve driver Doohan ahead of F1 season

-

Toulouse's Ntamack out of crunch Champions Cup match against Sale

Toulouse's Ntamack out of crunch Champions Cup match against Sale

-

US takes aim at Muslim Brotherhood in Arab world

-

Gloucester sign Springbok World Cup-winner Kleyn

Gloucester sign Springbok World Cup-winner Kleyn

-

Trump tells Iranians 'help on its way' as crackdown toll soars

-

Iran threatens death penalty for 'rioters' as concern grows for protester

Iran threatens death penalty for 'rioters' as concern grows for protester

-

US ends protection for Somalis amid escalating migrant crackdown

-

Oil prices surge following Trump's Iran tariff threat

Oil prices surge following Trump's Iran tariff threat

-

Fashion student, bodybuilder, footballer: the victims of Iran's crackdown

-

Trump tells Iranians to 'keep protesting', says 'help on its way'

Trump tells Iranians to 'keep protesting', says 'help on its way'

-

Italian Olympians 'insulted' by torch relay snub

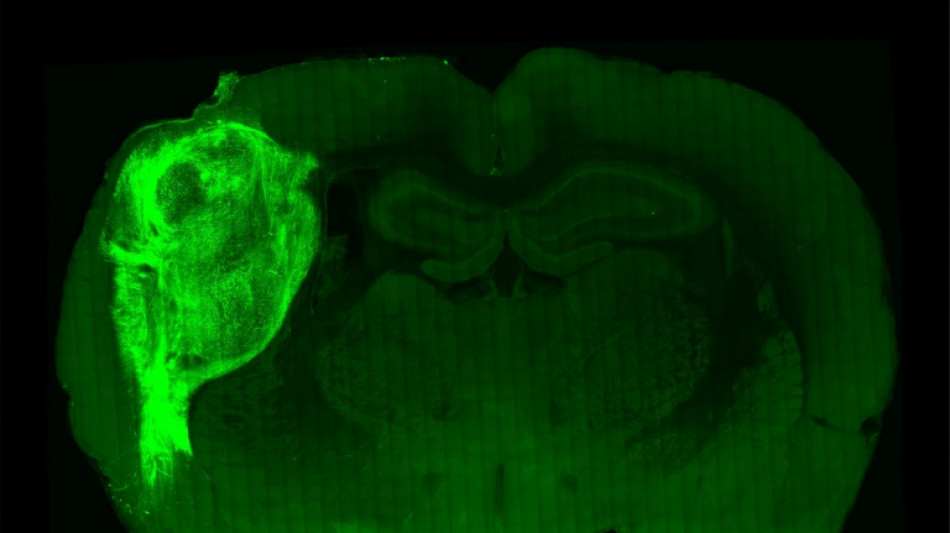

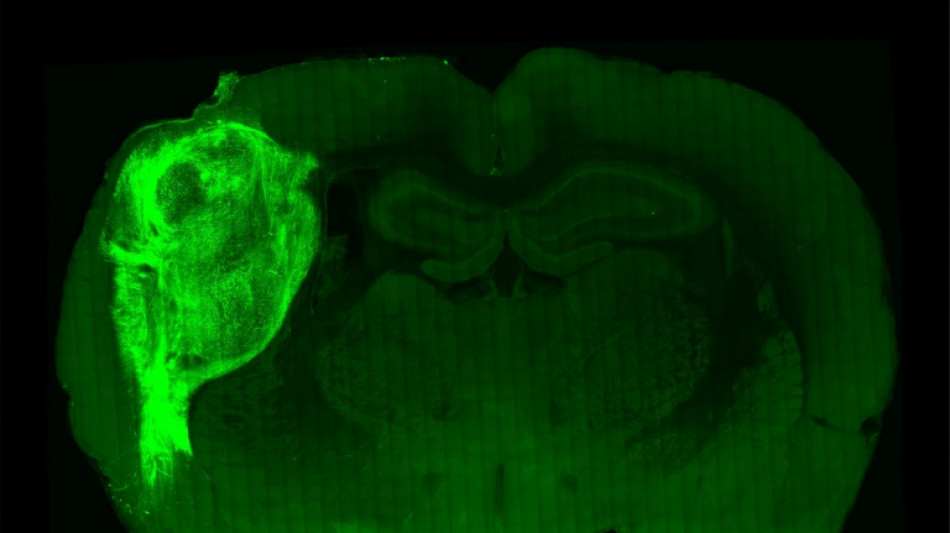

Human brain cells implanted in rats offer research gold mine

Scientists have successfully implanted and integrated human brain cells into newborn rats, creating a new way to study complex psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, and perhaps eventually test treatments.

Studying how these conditions develop is incredibly difficult -- animals do not experience them like people, and humans cannot simply be opened up for research.

Scientists can assemble small sections of human brain tissue derived from stem cells in petri dishes, and have already done so with more than a dozen brain regions.

But in dishes, "neurons don't grow to the size which a human neuron in an actual human brain would grow", said Sergiu Pasca, the study's lead author and professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at Stanford University.

And isolated from a body, they cannot tell us what symptoms a defect will cause.

To overcome those limitations, researchers implanted the groupings of human brain cells, called organoids, into the brains of young rats.

The rats' age was important: human neurons have been implanted into adult rats before, but an animal's brain stops developing at a certain age, limiting how well implanted cells can integrate.

"By transplanting them at these early stages, we found that these organoids can grow relatively large, they become vascularised (receive nutrients) by the rat, and they can cover about a third of a rat's (brain) hemisphere," Pasca said.

- Ethical dilemmas -

To test how well the human neurons integrated with the rat brains and bodies, air was puffed across the animals' whiskers, which prompted electrical activity in the human neurons.

That showed an input connection -- external stimulation of the rat's body was processed by the human tissue in the brain.

The scientists then tested the reverse: could the human neurons send signals back to the rat's body?

They implanted human brain cells altered to respond to blue light, and then trained the rats to expect a "reward" of water from a spout when blue light shone on the neurons via a cable in the animals' skulls.

After two weeks, pulsing the blue light sent the rats scrambling to the spout, according to the research published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The team has now used the technique to show that organoids developed from patients with Timothy syndrome grow more slowly and display less electrical activity than those from healthy people.

The technique could eventually be used to test new drugs, according to J. Gray Camp of the Roche Institute for Translational Bioengineering, and Barbara Treutlein of ETH Zurich.

It "takes our ability to study human brain development, evolution and disease into uncharted territory", the pair, who were not involved in the study, wrote in a review commissioned by Nature.

The method raises potentially uncomfortable questions -- how much human brain tissue can be implanted into a rat before the animal's nature is changed? Would the method be ethical in primates?

Pasca argued that limitations on how deeply human neurons integrate with the rat brain provide "natural barriers".

Rat brains develop much faster than human ones, "so there's only so much that the rat cortex can integrate".

But in species closer to humans, those barriers might no longer exist, and Pasca said he would not support using the technique in primates for now.

He argued though that there is a "moral imperative" to find ways to better study and treat psychiatric disorders.

"Certainly the more human these models are becoming, the more uncomfortable we feel," he said.

But "human psychiatric disorders are to a large extent uniquely human. So we're going to have to think very carefully... how far we want to go with some of these models moving forward."

V.Said--SF-PST