-

NFL names 49ers to face Rams in Aussie regular-season debut

NFL names 49ers to face Rams in Aussie regular-season debut

-

Bielle-Biarrey sparkles as rampant France beat Ireland in Six Nations

-

Flame arrives in Milan for Winter Olympics ceremony

Flame arrives in Milan for Winter Olympics ceremony

-

Olympic big air champion Su survives scare

-

89 kidnapped Nigerian Christians released

89 kidnapped Nigerian Christians released

-

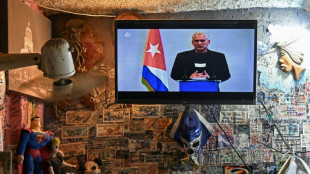

Cuba willing to talk to US, 'without pressure'

-

Famine spreading in Sudan's Darfur, UN-backed experts warn

Famine spreading in Sudan's Darfur, UN-backed experts warn

-

2026 Winter Olympics flame arrives in Milan

-

Congo-Brazzaville's veteran president declares re-election run

Congo-Brazzaville's veteran president declares re-election run

-

Olympic snowboard star Chloe Kim proud to represent 'diverse' USA

-

Iran filmmaker Panahi fears Iranians' interests will be 'sacrificed' in US talks

Iran filmmaker Panahi fears Iranians' interests will be 'sacrificed' in US talks

-

Leicester at risk of relegation after six-point deduction

-

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, raises calls to postpone Portugal vote

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, raises calls to postpone Portugal vote

-

Trump urges new nuclear treaty after Russia agreement ends

-

'Burned in their houses': Nigerians recount horror of massacre

'Burned in their houses': Nigerians recount horror of massacre

-

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate, affirms auto sector's future is electric

-

Emotional reunions, dashed hopes as Ukraine soldiers released

Emotional reunions, dashed hopes as Ukraine soldiers released

-

Bad Bunny promises to bring Puerto Rican culture to Super Bowl

-

Venezuela amnesty bill excludes gross rights abuses under Chavez, Maduro

Venezuela amnesty bill excludes gross rights abuses under Chavez, Maduro

-

Lower pollution during Covid boosted methane: study

-

Doping chiefs vow to look into Olympic ski jumping 'penis injection' claims

Doping chiefs vow to look into Olympic ski jumping 'penis injection' claims

-

England's Feyi-Waboso in injury scare ahead of Six Nations opener

-

EU defends Spain after Telegram founder criticism

EU defends Spain after Telegram founder criticism

-

Novo Nordisk vows legal action to protect Wegovy pill

-

Swiss rivalry is fun -- until Games start, says Odermatt

Swiss rivalry is fun -- until Games start, says Odermatt

-

Canadian snowboarder McMorris eyes slopestyle after crash at Olympics

-

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, disrupts Portugal vote

Deadly storm sparks floods in Spain, disrupts Portugal vote

-

Ukrainian flag bearer proud to show his country is still standing

-

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate

Carney scraps Canada EV sales mandate

-

Morocco says evacuated 140,000 people due to severe weather

-

Spurs boss Frank says Romero outburst 'dealt with internally'

Spurs boss Frank says Romero outburst 'dealt with internally'

-

Giannis suitors make deals as NBA trade deadline nears

-

Carrick stresses significance of Munich air disaster to Man Utd history

Carrick stresses significance of Munich air disaster to Man Utd history

-

Record January window for transfers despite drop in spending

-

'Burned inside their houses': Nigerians recount horror of massacre

'Burned inside their houses': Nigerians recount horror of massacre

-

Iran, US prepare for Oman talks after deadly protest crackdown

-

Winter Olympics opening ceremony nears as virus disrupts ice hockey

Winter Olympics opening ceremony nears as virus disrupts ice hockey

-

Mining giant Rio Tinto abandons Glencore merger bid

-

Davos forum opens probe into CEO Brende's Epstein links

Davos forum opens probe into CEO Brende's Epstein links

-

ECB warns of stronger euro impact, holds rates

-

Famine spreading in Sudan's Darfur, warn UN-backed experts

Famine spreading in Sudan's Darfur, warn UN-backed experts

-

Lights back on in eastern Cuba after widespread blackout

-

Russia, US agree to resume military contacts at Ukraine talks

Russia, US agree to resume military contacts at Ukraine talks

-

Greece aims to cut queues at ancient sites with new portal

-

No time frame to get Palmer in 'perfect' shape - Rosenior

No time frame to get Palmer in 'perfect' shape - Rosenior

-

Stocks fall as tech valuation fears stoke volatility

-

US Olympic body backs LA28 leadership amid Wasserman scandal

US Olympic body backs LA28 leadership amid Wasserman scandal

-

Gnabry extends Bayern Munich deal until 2028

-

England captain Stokes suffers facial injury after being hit by ball

England captain Stokes suffers facial injury after being hit by ball

-

Italy captain Lamaro amongst trio set for 50th caps against Scotland

Time machine: How carbon dating brings the past back to life

From unmasking art forgery to uncovering the secrets of the Notre-Dame cathedral, an imposing machine outside Paris can turn back the clock to reveal the truth.

It uses a technique called carbon dating, which has "revolutionised archaeology", winning its discoverer a Nobel Prize in 1960, French scientist Lucile Beck said.

She spoke to AFP in front of the huge particle accelerator, which takes up an entire room in the carbon dating lab of France's Atomic Energy Commission in Saclay, outside the capital.

Beck described the "surprise and disbelief" among prehistorians in the 1990s when the machine revealed that cave art in the Chauvet Cave in France's southeast was 36,000 years old.

The laboratory uses carbon dating, also called carbon-14, to figure out the timeline of more than 3,000 samples a year.

- So how does it work? -

First, each sample is examined for any trace of contamination.

"Typically, they are fibres from a jumper" of the archaeologist who first handled the object, Beck said.

The sample is then cleaned in an acid bath and heated to 800 degrees Celsius (1,472 Fahrenheit) to recover its carbon dioxide. This gas is then reduced to graphite and inserted into tiny capsules.

Next, these capsules are put into the particle accelerator, which separates their carbon isotopes.

Isotopes are variants of the same chemical element which have different numbers of neutrons.

Some isotopes are stable, such as carbon-12. Others -- such as carbon-14 -- are radioactive and decay over time.

Carbon-14 is constantly being created in Earth's upper atmosphere as cosmic rays and solar radiation bombard the chemical nitrogen.

In the atmosphere, this creates carbon dioxide, which is absorbed by plants during photosynthesis.

Then animals such as ourselves get in on the act by eating those plants.

So all living organisms contain carbon-14, and when they die, it starts decaying. Only half of it remains after 5,730 years.

After 50,000 years, nothing is left -- making this the limit on how far back carbon dating can probe.

By comparing the number of carbon-12 and carbon-14 particles separated by the particle accelerator, scientists can get an estimate of how old something is.

Cosmic radiation is not constant, nor is the intensity of the magnetic field around Earth protecting us from it, Beck said.

That means scientists have to make estimations based on calculations using samples whose ages are definitively known.

This all makes it possible to spot a forged painting, for example, by demonstrating that the linen used in the canvas was harvested well after when the purported painter died.

The technique can also establish the changes in our planet's climate over the millennia by analysing the skeletons of plankton found at the bottom of the ocean.

- Notre-Dame revealed -

Carbon dating can be used on bones, wood and more, but the French lab has developed new methods allowing them to date materials that do not directly derive from living organisms.

For example, they can date the carbon that was trapped in iron from when its ore was first heated by charcoal.

After Paris's famous Notre-Dame cathedral almost burned to the ground in 2019, this method revealed that its big iron staples dated back to when it was first built -- and not to a later restoration, as had been thought.

The technique can also analyse the pigment lead white, which has been painted on buildings and used in artworks across the world since the fourth century BC.

To make this pigment, "lead was corroded with vinegar and horse poo, which produces carbon dioxide through fermentation," Beck explained.

She said she always tells archaeologists: "don't clean traces of corrosion, they also tell about the past!"

Another trick made it possible to date the tombs of a medieval abbey in which only small lead bottles had been found.

As the bodies in the tombs decomposed, they released carbon dioxide, corroding the bottles and giving scientists the clue they needed.

"This corrosion was ultimately the only remaining evidence of the spirit of the monks," Beck mused.

J.AbuHassan--SF-PST