-

Snowstorm blankets US northeast as New York sees travel ban

Snowstorm blankets US northeast as New York sees travel ban

-

Healthcare crisis looms over Greenland's isolated villages

-

Hodgkinson says breaking 800m record would put her among athletics' greatest

Hodgkinson says breaking 800m record would put her among athletics' greatest

-

Two Russian security personnel were on board France-seized tanker: sources

-

EU puts US trade deal on ice after Supreme Court ruling

EU puts US trade deal on ice after Supreme Court ruling

-

Hetmyer blasts 85 as West Indies pile up 254-6 against Zimbabwe

-

Canada PM heads to Asia seeking new trade partners as US ties fray

Canada PM heads to Asia seeking new trade partners as US ties fray

-

South Africa accepts Trump's new US ambassador

-

Iraq's Maliki defends PM candidacy, seeks to reassure US

Iraq's Maliki defends PM candidacy, seeks to reassure US

-

UEFA suspend Benfica's Prestianni after alleged racist abuse

-

Jetten sworn in as youngest-ever Dutch PM

Jetten sworn in as youngest-ever Dutch PM

-

Italy's Enel to invest 20bn euros in renewables by 2028

-

BBC apologises for 'involuntary' Tourette's racial slur during BAFTA awards

BBC apologises for 'involuntary' Tourette's racial slur during BAFTA awards

-

Kristen Bell returns to host glitzy Actor Awards in Hollywood

-

Iran says would respond 'ferociously' to any US attack

Iran says would respond 'ferociously' to any US attack

-

Venezuelan foreign minister demands 'immediate release' of Maduro

-

Dane Vingegaard to start season at Paris-Nice in March

Dane Vingegaard to start season at Paris-Nice in March

-

Australia PM backs removing UK's Andrew from line of succession

-

Where do Ukraine and Russia stand after four years of war?

Where do Ukraine and Russia stand after four years of war?

-

Police investigating racist abuse of Premier League quartet

-

Fiji to start Nations Championship at 'home' to Wales in Cardiff

Fiji to start Nations Championship at 'home' to Wales in Cardiff

-

EU lawmakers to put US trade deal on hold after Supreme Court ruling

-

Rubio to attend Caribbean summit as US presses Venezuela, Cuba

Rubio to attend Caribbean summit as US presses Venezuela, Cuba

-

'Ugly' England aim to spin their way to T20 World Cup semi-finals

-

Nigeria paid Boko Haram ransom for kidnapped pupils: intel sources

Nigeria paid Boko Haram ransom for kidnapped pupils: intel sources

-

Tudor says Tottenham can still beat the drop despite Arsenal loss

-

Violence sweeps Mexico after most-wanted drug cartel leader killed

Violence sweeps Mexico after most-wanted drug cartel leader killed

-

France giant Meafou capable of being 'world's best' lock

-

Stocks diverge, dollar down over Trump tariffs uncertainty

Stocks diverge, dollar down over Trump tariffs uncertainty

-

World champions South Africa announce eight home Tests for 2026/27

-

Liverpool boss Slot encouraged by Mac Allister's return to form

Liverpool boss Slot encouraged by Mac Allister's return to form

-

India replaces British architect statue with independence hero

-

Pakistan warn England's flaky batting to expect a trial by spin

Pakistan warn England's flaky batting to expect a trial by spin

-

Philippines' Duterte authorised murders, ICC told as hearings open

-

Iran says would respond 'ferociously' to any US attack, even limited strikes

Iran says would respond 'ferociously' to any US attack, even limited strikes

-

New Dutch government sworn in under centrist Jetten

-

What the future holds for the CJNG cartel after leader killed

What the future holds for the CJNG cartel after leader killed

-

ICC kicks off pre-trial hearing over Philippines' Duterte

-

UN chief decries global rise of 'rule of force'

UN chief decries global rise of 'rule of force'

-

Nemesio Oseguera, the brutal Mexican drug lord known as 'El Mencho'

-

Senegal's Sahad, radiant champion of 'musical pan-Africanism'

Senegal's Sahad, radiant champion of 'musical pan-Africanism'

-

New York orders citywide travel ban as major storm hits US

-

'Considered a traitor': Life of an anti-war Ukrainian in Russia

'Considered a traitor': Life of an anti-war Ukrainian in Russia

-

South Korea and Brazil sign deals on K-beauty, trade

-

Zimbabwe farmers seek US help over long-promised payouts

Zimbabwe farmers seek US help over long-promised payouts

-

Hong Kong appeals court upholds jailing of 12 democracy campaigners

-

India battle for World Cup survival after 'messing up on grand scale'

India battle for World Cup survival after 'messing up on grand scale'

-

'I will go': Bengalis in Pakistan hope for family reunions

-

North Korea touts nuclear advances as Kim re-chosen to lead ruling party

North Korea touts nuclear advances as Kim re-chosen to lead ruling party

-

South Korea protests 'Victory' banner hung from Russian embassy

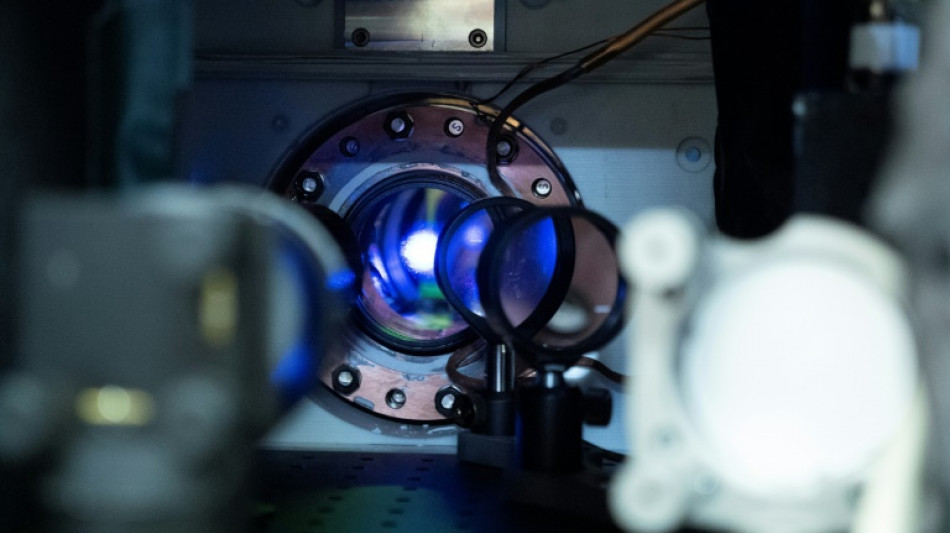

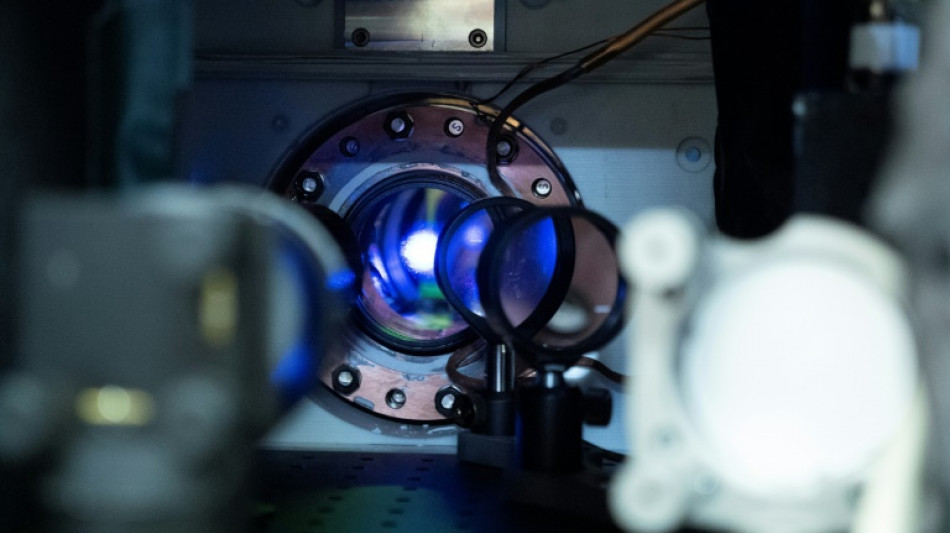

How world's most precise clock could transform fundamental physics

US scientists have measured Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity -- which holds that gravity slows time down -- at the smallest scale ever, demonstrating that clocks tick at different rates when separated by fractions of a millimeter.

Jun Ye, of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder, told AFP it was "by far" the most precise clock ever built -- and could pave the way for new discoveries in quantum mechanics, the rulebook for the subatomic world.

Ye and colleagues published their findings in the prestigious journal Nature on Wednesday, describing the engineering advances that enabled them to build a device 50 times more precise than their previous best clock, itself a record-breaker, built in 2010.

It was more than a century ago, in 1915, that Einstein put forward his theory of general relativity, which held that the gravitational field of a massive object distorts space-time.

This causes time to move more slowly as one approaches closer to the object.

But it wasn't until the invention of atomic clocks -- which keep time by detecting the transition between two energy states inside an atom exposed to a particular frequency -- that scientists could prove the theory.

Early experiments included the Gravity Probe A of 1976, which involved a spacecraft six thousand miles (10,000 kilometers) above Earth's surface and showed that an onboard clock was faster than an equivalent on Earth by one second every 73 years.

Since then, clocks have become more and more precise, and thus better able to detect the effects of relativity.

A decade ago, Ye's team set a record by observing time moving at different rates when their clock was moved 33 centimeters (just over a foot) higher.

- Theory of everything -

Ye's key breakthrough was working with webs of light, known as optical lattices, to trap atoms in orderly arrangements. This is to stop the atoms from falling due to gravity or otherwise moving, resulting in a loss of accuracy.

Inside Ye’s new clock are 100,000 strontium atoms, layered on top of each other like a stack of pancakes, in total about a millimeter high.

The clock is so precise that when the scientists divided the stack into two, they could detect differences in time in the top and bottom halves.

At this level of accuracy, clocks essentially act as sensors.

"Space and time are connected," said Ye. "And with time measurement so precise, you can actually see how space is changing in real time -- Earth is a lively, living body."

Such clocks spread out over a volcanically-active region could tell geologists the difference between solid rock and lava, helping predict eruptions.

Or, for example, study how global warming is causing glaciers to melt and oceans to rise.

What excites Ye most, however, is how future clocks could usher in a completely new realm of physics.

The current clock can detect time differences across 200 microns -- but if that was brought down to 20 microns, it could start to probe the quantum world, helping bridge gaps in theory.

While relativity beautifully explains how large objects like planets and galaxies behave, it is famously incompatible with quantum mechanics, which deals with the very small, and holds that everything can behave like a particle and a wave.

The intersection of the two fields would bring physics a step closer to a unifying "theory of everything" that explains all physical phenomena of the cosmos.

B.AbuZeid--SF-PST