-

Stellantis takes massive hit for 'overestimation' of EV shift

Stellantis takes massive hit for 'overestimation' of EV shift

-

'Mona's Eyes': how an obscure French art historian swept the globe

-

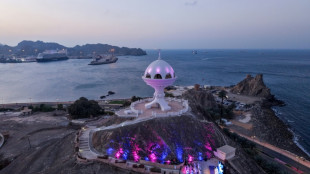

Iran, US hold talks in Oman

Iran, US hold talks in Oman

-

Iran, US hold talks in Oman after deadly protest crackdown

-

In Finland's forests, soldiers re-learn how to lay anti-personnel mines

In Finland's forests, soldiers re-learn how to lay anti-personnel mines

-

Israeli president visits Australia after Bondi Beach attack

-

In Dakar fishing village, surfing entices girls back to school

In Dakar fishing village, surfing entices girls back to school

-

Lakers rally to beat Sixers despite Doncic injury

-

Russian pensioners turn to soup kitchen as war economy stutters

Russian pensioners turn to soup kitchen as war economy stutters

-

Japan taps Meta to help search for abuse of Olympic athletes

-

As Estonia schools phase out Russian, many families struggle

As Estonia schools phase out Russian, many families struggle

-

Toyota names new CEO, hikes profit forecasts

-

Next in Putin's sights? Estonia town stuck between two worlds

Next in Putin's sights? Estonia town stuck between two worlds

-

Family of US news anchor's missing mother renews plea to kidnappers

-

Spin woes, injury and poor form dog Australia for T20 World Cup

Spin woes, injury and poor form dog Australia for T20 World Cup

-

Japan's Liberal Democratic Party: an election bulldozer

-

Hazlewood out of T20 World Cup in fresh blow to Australia

Hazlewood out of T20 World Cup in fresh blow to Australia

-

Japan scouring social media 24 hours a day for abuse of Olympic athletes

-

Bangladesh Islamist leader seeks power in post-uprising vote

Bangladesh Islamist leader seeks power in post-uprising vote

-

Rams' Stafford named NFL's Most Valuable Player

-

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

Japan to restart world's biggest nuclear plant

-

Japan's Sanae Takaichi: Iron Lady 2.0 hopes for election boost

-

Italy set for 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony

Italy set for 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony

-

Hong Kong to sentence media mogul Jimmy Lai on Monday

-

Pressure on Townsend as Scots face Italy in Six Nations

Pressure on Townsend as Scots face Italy in Six Nations

-

Taiwan's political standoff stalls $40 bn defence plan

-

Inter eyeing chance to put pressure on title rivals Milan

Inter eyeing chance to put pressure on title rivals Milan

-

Arbeloa's Real Madrid seeking consistency over magic

-

Dortmund dare to dream as Bayern's title march falters

Dortmund dare to dream as Bayern's title march falters

-

PSG brace for tough run as 'strange' Marseille come to town

-

Japan PM wins Trump backing ahead of snap election

Japan PM wins Trump backing ahead of snap election

-

AI tools fabricate Epstein images 'in seconds,' study says

-

Asian markets extend global retreat as tech worries build

Asian markets extend global retreat as tech worries build

-

Sells like teen spirit? Cobain's 'Nevermind' guitar up for sale

-

Thailand votes after three prime ministers in two years

Thailand votes after three prime ministers in two years

-

UK royal finances in spotlight after Andrew's downfall

-

Diplomatic shift and elections see Armenia battle Russian disinformation

Diplomatic shift and elections see Armenia battle Russian disinformation

-

Undercover probe finds Australian pubs short-pouring beer

-

Epstein fallout triggers resignations, probes

Epstein fallout triggers resignations, probes

-

The banking fraud scandal rattling Brazil's elite

-

Party or politics? All eyes on Bad Bunny at Super Bowl

Party or politics? All eyes on Bad Bunny at Super Bowl

-

Man City confront Anfield hoodoo as Arsenal eye Premier League crown

-

Patriots seek Super Bowl history in Seahawks showdown

Patriots seek Super Bowl history in Seahawks showdown

-

Gotterup leads Phoenix Open as Scheffler struggles

-

In show of support, Canada, France open consulates in Greenland

In show of support, Canada, France open consulates in Greenland

-

'Save the Post': Hundreds protest cuts at famed US newspaper

-

New Zealand deputy PM defends claims colonisation good for Maori

New Zealand deputy PM defends claims colonisation good for Maori

-

Amazon shares plunge as AI costs climb

-

Galthie lauds France's remarkable attacking display against Ireland

Galthie lauds France's remarkable attacking display against Ireland

-

Argentina govt launches account to debunk 'lies' about Milei

What are attoseconds? Nobel-winning physics explained

The Nobel Physics Prize was awarded on Tuesday to three scientists for their work on attoseconds, which are almost unimaginably short periods of time.

Their work using lasers gives scientists a tool to observe and possibly even manipulate electrons, which could spur breakthroughs in fields such as electronics and chemistry, experts told AFP.

- How fast are attoseconds? -

Attoseconds are a billionth of a billionth of a second.

To give a little perspective, there are around as many attoseconds in a single second as there have been seconds in the 13.8-billion year history of the universe.

Hans Jakob Woerner, a researcher at the Swiss university ETH Zurich, told AFP that attoseconds are "the shortest timescales we can measure directly".

- Why do we need such speed? -

Being able to operate on this timescale is important because these are the speeds at which electrons -- key parts of an atom -- operate.

For example, it takes electrons 150 attoseconds to go around the nucleus of a hydrogen atom.

This means the study of attoseconds has given scientists access to a fundamental process that was previously out of reach.

All electronics are mediated by the motion of electrons -- and the current "speed limit" is nanoseconds, Woerner said.

If microprocessors were switched to attoseconds, it could be possible to "process information a billion times faster," he added.

- How do you measure them? -

Franco-Swede physicist Anne L'Huillier, one of the three new Nobel laureates, was the first to discover a tool to pry open the world of attoseconds.

It involves using high-powered lasers to produce pulses of light for incredibly short periods.

Franck Lepine, a researcher at France's Institute of Light and Matter who has worked with L'Huillier, told AFP it was like "cinema created for electrons".

He compared it to the work of pioneering French filmmakers the Lumiere brothers, "who cut up a scene by taking successive photos".

John Tisch, a laser physics professor at Imperial College London, said that it was "like an incredibly fast, pulse-of-light device that we can then shine on materials to get information about their response on that timescale".

- How low can we go? -

All three of Tuesday's laureates at one point held the record for shortest pulse of light.

In 2001, French scientist Pierre Agostini's team managed to flash a pulse that lasted just 250 attoseconds.

L'Huillier's group beat that with 170 attoseconds in 2003.

In 2008, Hungarian-Austrian physicist Ferenc Krausz more than halved that number with an 80-attosecond pulse.

The current holder of the Guinness World Record for "shortest pulse of light" is Woerner's team, with a time of 43 attoseconds.

The time could go as low as a few attoseconds using current technology, Woerner estimated. But he added that this would be pushing it.

- What could the future hold? -

Technology taking advantage of attoseconds has largely yet to enter the mainstream, but the future looks bright, the experts said.

So far, scientists have mostly only been able to use attoseconds to observe electrons.

"But what is basically untouched yet -- or is just really beginning to be possible -- is to control" the electrons, to manipulate their motion, Woerner said.

This could lead to far faster electronics as well as potentially spark a revolution in chemistry.

So-called "attochemistry" could lead to more efficient solar cells, or even the use of light energy to produce clean fuels, he added.

L.AbuTayeh--SF-PST